The Ocean Liners 1913-1942, a Transatlantic Aesthetic exhibition explores the role the new giants of the sea played in developing an international modernist aesthetic. The Musée d’arts de Nantes and the Musée d’art moderne André Malraux-Le Havre present a new take on the great transatlantic history of the ports of Nantes-Saint-Nazaire and Le Havre.

The roaring twenties were the golden age for ocean liners, as much floating palaces as modern machines with their tapered design. At the time they were the only real link between old Europe and the United States. With the various Immigration Acts (1917 and 1924) limiting migration to the United States, followed by the Great Depression of 1929, the main companies sought out a leisure clientèle, which included intellectuals, writers and artists seeking exchange with the other continent. The ocean liner is a paradoxical object, briefly embodying the dream of transatlantic modernity. Within that mobile building, with state-of-the-art machinery devoted to speed within a luxury holiday resort, various nationalities and different social classes rub shoulders during the crossing. The first part of the exhibition shows that the ocean liner as an object itself fascinated avant-garde circles, from photographs to architects, painters and poster designers. The second part studies the experience of the voyage, between the understated luxury of the Art Deco interiors, the life of open-air leisure on the decks, and more deeply, the strange experience of life on board a stateless microcosm, isolated and moving through the open seas, retold by the literature and cinema of the era.

PART 1: OCEAN LINER, A MODERNIST OBJECT

A. Photography and advertising: the international language of ocean liners

In the 1920s and 1930s, the competition to attract and retain a luxury clientele for Atlantic crossings was fierce. This competition was heightened by geopolitical tensions from the 1930s onwards, making ocean liners an important strategic concern. Technological flagships and showcases of increasingly advanced engineering, they embodied the power of a nation. Germany, with Europa (1928) and Bremen (1929), Italy with Rex and Conte di Savoia (launched together in 1931), Great Britain with the Queen Mary (1934) and France with Normandie (1935) competed to take the prestigious “Blue Riband”, the unofficial award for the fastest crossing of the North Atlantic. The national and international press, with patriotic overtones, was bowled over by these maritime battles. The combined political and economic climate explains the plethora of advertisements, magazine covers, posters and presentation brochures. The imagery of ocean liners was inspired by a shared international language, crossing over between the arts, the press and advertising. The brilliant poster artist Cassandre was without doubt one of the most iconic representatives of this international aesthetic.

1. Posters and national rivalries

In the field of transatlantic advertising, the poster artist Cassandre, with Paul Colin and Jean Auvigné, stood out in France with the restraint of their compositions, which were almost architectural, with a bold interplay between graphics and image. In terms of photography and posters, the period was dominated by geometric forms, influenced by the great artistic movements of futurism, purism and Bauhaus aesthetics. The close-ups of bows and smokestacks embody the graphics of the conquering power of ships. The majority of the companies (in Italy, Germany and Great Britain) adopted these over-sized motifs, often lending them their national colors to promote their fleets. The circulation of these images, with the clean and highly modern graphics, marked the emergence of a shared international language around the imagery of ocean liners.

2. A revolution in photography

Born in the 19th century with the industrial revolution, photography accompanied the technological progress of the interwar period. The perfecting of printing and shooting techniques (with the Leica I and Rolleiflex cameras, lighter and more practical) allowed photographers to do new, more creative and graphic types of framing, highlighting the over-sized representations and dynamics of the bows and smokestacks. The shipping companies, starting with the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique, and the magazines seized these daring shots that seduced the public. Followed on each step of its journey, from the shipyard to its inaugural crossing, the saga of the Normandie ocean liner marked the rise of the most avant-garde photographs, including the New Vision. They became a source of inspiration for painters such as Jules Lefranc, who borrowed their framing in his works.

3. Ocean liners, a paragon for modernist architecture

“The house of the earth-man is the expression of a circumscribed world. The steamship is the first stage in the realization of a world organized according to the new spirit.” In the conclusion of his chapter “Eyes which do not see. I. Liners” (Towards a New Architecture, 1923 and 1927 for its first english translation), Le Corbusier summarizes the promise embodied by ocean liners for the renewal of the architectural aesthetic. Although the decorative classicism of the interiors disappointed the most innovative architects, the perfection of the aerodynamic lines and the powerful machines, visible from the docks and on the decks, was a source of inspiration for modernist architects and designers such as Robert MalletStevens (La Pergola Casino at Saint-Jean-de-Luz) or Eileen Gray (E-1027 House by the Sea).

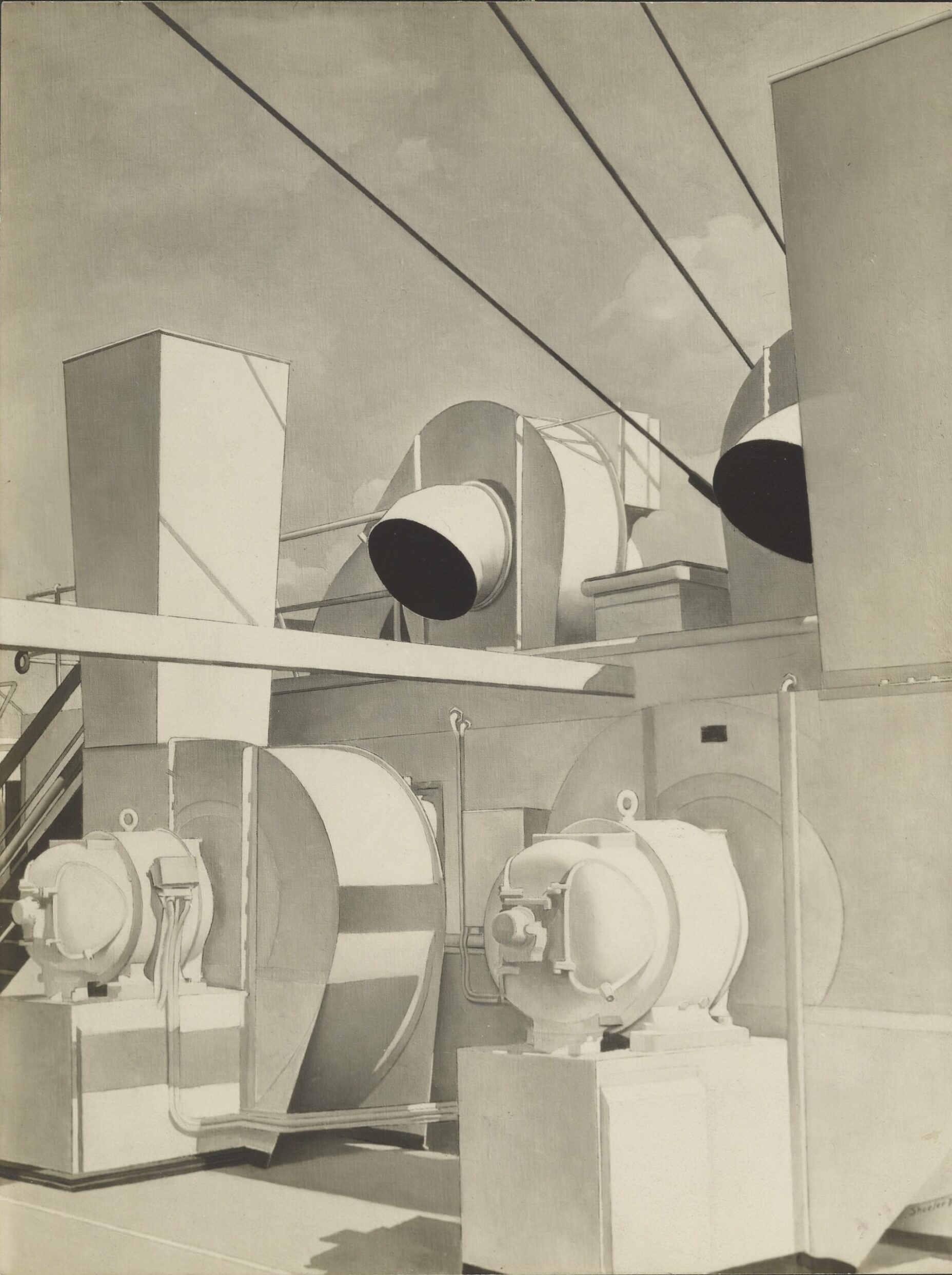

B. OCEAN LINER, the beauty of the machine

A total work of art in the minds of many designers, combining nautical aerodynamics with architecture, decor and furnishings, the ocean liner was a source of inspiration for avant-garde artists, who represented it to the point of obsession. In the words of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in 1909 in his Manifesto of Futurism: “Alone with the engineers in the infernal stokeholes of great ships, […] we will sing […] the nocturnal vibration of the arsenals and the workshops beneath their violent electric moons; […] adventurous steamers sniffing the horizon.” On the heels of the poster artists, painters (Fernand Léger, Charles Demuth, Irene Rice Pereira), photographers (Pierre Boucher, Roger Schall, Jean Moral and René Zuber) and cinematographers (Walter Ruttmann) from all countries appropriated the image of these giants of the seas. These artists and designers, sometimes connected to one another, rubbed shoulders in associations such as the UAM (French union of modern artists), created in 1929. Drawing on their rich experiences, they explored the tapered lines with their menacing monumentality, or deconstructed the perfection of the machinery in minute detail, sometime to abstraction.

Paquebot, Charles Demuth, 1921-1922

1. Machines, shipyards and modernity

Photographers, whether artists, photo-journalists or engineers, were the closest witnesses to the modern industrialized world. Their shots place shipyards and port districts, partway between the city and the ocean, on a footing with true urban landscapes. Through their lenses they became unusual and somewhat magical places in which ocean liners rise up from nothingness, among the metal outlines of great cranes. Artists also went down to the holds and machine rooms to find new and fascinating subjects for their artworks. Painters such as Irene Rice Pereira and Fernand Léger wholeheartedly appropriated the mechanized perfection of the engines, pistons and propellers, and extolled their beauty in simple, colorful geometric forms.

2. Fragments of ocean liners: towards abstraction

Several avant-garde artists (futurists, cubists and purists) were passionate about ocean liners, the embodiment of the modernity of an urban and technological civilization, but also the link between “Old Europe” and the promise of the American “New World”. The graphic line of the ocean liner’s silhouette, the circular rhythm of the portholes and rivets on its side walls and the tubular curve of the smokestacks, reconcile the quest for realism with the purest type of formalism. This helps us understand the irresistible allure it had for the greatest representatives of American precisionism, such as Charles Demuth and Charles Sheeler, or for photographers such as Walker Evans and François Tuefferd. Through bright and intense lighting, and geometric fragmentation of the image, the technical details blend with the trend towards abstraction.

PART 2: THE TRANSATLANTIC VOYAGE

A. The ocean liner, a floating palace

A giant, static temple in the port, the ocean liner became a fragile vessel buffeted by waves on the ocean. All efforts were made to transform it into a reassuring luxury Art Deco hotel once passengers crossed its threshold. Its passengers came from all walks of life, from the wealthiest to the most modest. This microsociety on board was multi-cultural but strictly separated by class. Although passengers did not all travel in the same conditions, depending on their class on board, they shared the same experience of the sea, by turns exhilarating, delightful, harrowing and terrifying. And the shipping companies did their best to make them forget this by offering all kinds of distractions, including relaxation, games, reading, fine dining, shows and dance. The European shipping companies were up against fierce competition where speed was part of the sale pitch, whereas the French companies, in particular the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique (CGT), focused more on the lifestyle and the highly luxurious interiors in first class.

1. An Art Deco showcase

An Art Deco masterpiece, the Normandie was the biggest and most luxurious ocean liner when it was launched. It managed to blend a daring technicality with state-of-the-art decorative arts. Decorators and artists (Jean Dupas, Jean Dunand and Jacques-Charles Champigneulle) received the most prestigious orders, particularly for the first class areas, which predominated on board. Gold and silver sparkled beneath the lights of the grand hall and the smoking lounge. The lavishness of the decor went hand in hand with that of the tableware, with silverware from the “Transat” service by Luc Lanel, the artistic director at Christofle, and glassware by Suzanne Lalique-Haviland.

2. Fashion and life on board

The interior spaces of ocean liners were designed to resemble floating palaces, adopting the aesthetic elements of grand hotels on land. This lavish environment contrasted sharply with the extreme austerity of the exterior. A variety of activities and leisure offerings were available to first-class passengers, to help ward off any boredom they may experience during the four or five days of the crossing. The promenade deck and the gangways became the backdrop for clay pigeon shooting, tennis, shuffleboard, races and a variety of games where passengers donned very modern outfits for the period, including bathing suits, pajamas, shorts and sailor suits during the day. Cruise sportswear, as well as seaside resort and luxury yachting fashions, were on display. Dinners offered up a procession of elegant outfits, from haute couture fashion houses such as Coco Chanel, Jeanne Paquin, Jeanne Lanvin, Jean Patou, Christian Dior and others.

B. The crossing

“Ocean travel is enchanting. You don’t just travel, you live the journey. The journey is not an action but rather a meditation, a state, a revelation that the simple fact of existing is a true joy” (Blaise Cendrars). During the interwar period, the idea of avant-garde seemed inseparable from that of travel, and biographies of many writers, painters and photographers seemed to confirm it. Even though they were often forced to travel, temporarily or permanently, driven by poverty or by history, artists traveling far from their place of origin and culture experienced meetings and enrichment of which the crossing was just the beginning.

1. The experience of the voyage

The world of the ocean liner, a grand yet insignificant presence on the ocean, blurred the lines between time and space (Jean-Émile Laboureur), becoming a place where everything was possible, with an often existential and cosmopolitan experience. With nationalism on the rise, transatlantic crossings allowed passengers to become stateless, and an entire generation of traveling artists were able to distance themselves from their native land. The crossing itself became an initiatory odyssey towards another continent, a promise of renewal for the artists. For Joaquín Torres-García, ocean liners embodied this cultural tie, a mirror of his dual Catalan-Uruguay nationality. Between 1915 and 1955, Marcel Duchamp boarded transatlantic liners 19 times, driven by wars but above all by his “expatriate spirit” – this modern vision of travel which uproots to allow a rebirth – and which led him to split his time between Paris and New York.

2. The arrival in New York from the ocean

All journeys to the United States invariably began with the arrival by sea at the port of New York, and the Manhattan skyline. This experience of a vertical island-city sitting on the water, for travelers and European immigrants alike, summed up the arrival in the New World, the prestige of the architectural and technological modernity that it represented, the essence of the city and of modern living. Of his first trip to New York in 1931, Fernand Léger wrote: “After a six-day crossing in the fluid, elusive, moving and gentle water, we arrive before this steep mountain, created by men, slowly revealing itself and growing clearer, its sharp edges coming into focus, its windows in order, its metallic color. It rises up ferociously above the sea level. The ship turns… it disappears slowly, glinting in profile like a suit of armor.” The works of Raoul Dufy and Amédée Ozenfant, photographs from famous names such as Berenice Abbott or commercial photographers, describe this connection between the ocean liner and the big American city.

Epilogue: fleeing Europe

The exhibition’s epilogue closes this enchanted interlude with a tragic era where the ocean liner becomes the instrument of exile, following the rise of totalitarianism (with Stalin’s rise to power in the USSR in 1927 and above all the installation of the Nazi regime in 1933 in Germany). For the passenger, the crossing was an extraordinary experience, a stateless interlude where certain social rules were temporarily suspended, and it became a place of uncertainty and a painful displacement. This is illustrated by a series of works by Lasar Segall, Marcel Duchamp and Kay Sage, and by two vivid photographic documentaries: the impossible anchoring of the Saint-Louis in 1939, in Cuba, and the sinking of the Normandie in the port of New York in 1942.

Crossings…

The unity of place and time inherent in this closed, moving ocean liner enabled some modern audaciousness and the mixing of social worlds, as recounted by amateurs, writers and cinematographers: Charlie Chaplin , The Immigrant, 1917, Buster Keaton, The Navigator, 1924; Man Ray, The Starfish, 1928, Leo McCarey, An Affair to Remember, 1939, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Tristes Tropiques, 1955; Blaise Cendrars, L’Équateur, Louis Chadourne, La Désirade. The exhibition features a space dedicated to these experiments, allowing visitors to get close to the experience of an ocean crossing, surrounded by three projections of archive images, quotations, amateur documentaries and extracts of Hollywood films. Views of the Atlantic in all its states make the connection between the ocean liner and the horizon, between togetherness and feelings of solitude, between silence and the hubbub of the machines, between the calm and the storm. Ten minutes of immersion to capture this crossing that sparked the imagination of the roaring twenties.